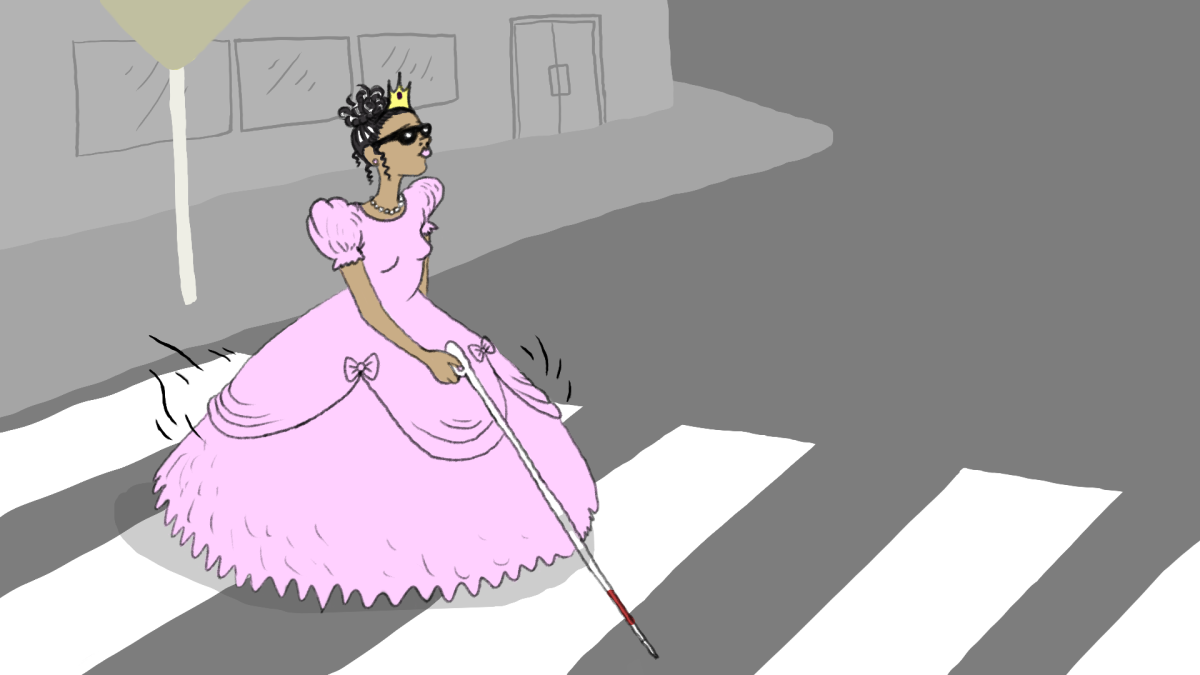

Nothing is more dreadful than the long walk to an exam. As you walk between roads and crosswalks, you find yourself not looking to see if there’s any oncoming traffic. When there are cars, or the hard-to-miss Wolfline, you think in defiance: “Hit me. Make my day. Pay my tuition.” The “pay my college tuition walk” is a common joke heard around campuses throughout the nation.

The premise behind it? Once you’re hit by a school-affiliated bus, then you have tuition and medical bills paid for by the university, or if it’s a car, then you win in court and secure your rightful money. But contrary to the myth, in North Carolina courts, those hit must prove they did not contribute to the accident and that it was only the responsibility of the driver, according to Fran Lewis Muse, a director and attorney at the Carolina Student Legal Services.

Yet, one of the first rules taught in driver’s education courses is that the pedestrian always has the right of way, so it makes sense that students could walk wherever they want on the road and force drivers to cater to them. Although it’s true students do have the right of way, it doesn’t give us the right to walk whenever we want.

For example, the traffic lights at the intersection of Morrill Drive and Cates Avenue have a preinstalled pedestrian crossing system which notifies walkers, bikers, and other pedestrians when they can cross the intersection safely without worry of any cars moving. Instead, students calmly walk across the intersection even while the pedestrian signal is a bright orange “stop” hand, while, even though they have a green light, oncoming traffic has to wait.

The general apathy among students at these intersections shows a subtle sense of entitlement that puts more than just them in danger. A driver’s reaction may cause other unintended damage. Even if students are late or in a hurry to get somewhere, getting to class on time does not outweigh the importance of safety.

Although that intersection, and most of the intersections on Hillsborough have pedestrian signals, some other crossings at NC State do not. Another example known for frequent almost-collisions is the intersection between Cates Avenue and Jeter Drive. At this intersection, traffic is meant to flow naturally into Cates Avenue. Hence, traffic usually doesn’t feel the need to stop, and neither do students.

So, for this instance, how can collisions be prevented between unstoppable traffic and immovable students? Most scenarios that safely allow both parties to get where they need to go involve the awkward game of “You go” followed by “No, you go.”

Although it’s frustrating to do stutter-steps at every crosswalk while you wait for the single-hand flick that the driver gives for the pedestrian to go, this is one of the safest ways to allow pedestrians to cross. Not to mention, it still acknowledges that the driver is equal to the pedestrian rather than the crosser expecting the traffic to cater to them. Neither pedestrians nor drivers should ever speed up to “beat” their opponent to the crossing, as this can easily end in an accident.

Safe pedestrian practices begin on NC State’s campus and are diffused throughout the entire state when we enter the greater community as leaders in all fields: transportation safety included. Traffic patterns are a two-way street (pun intended) where both drivers and pedestrians alike need to work together to maximize safety and minimize risk. Remember, walking to class shouldn’t classify as a life-or-death scenario, and it probably won’t pay your tuition.