Barbara Sherry knows one in five of you reading this paper will have a heart infection at some point in your life. A few of you may even perish from such an infection. However, most of you will never know your heart was in any danger at all.

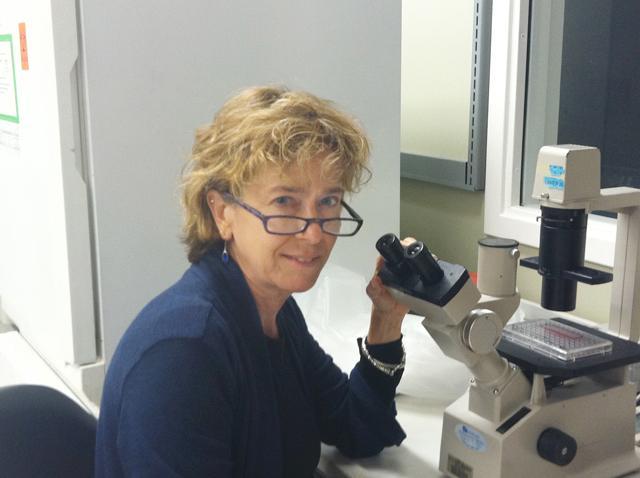

Sherry, a professor of virology at the College of Veterinary Medicine, recently received a $1.8 million grant to continue her research on how the heart manages to protect itself from the onslaught of viruses people encounter every day.

According to Sherry, viruses have two common methods for targeting the body’s tissues. Viruses, like rabies and herpes simplex 1, infect a body by way of its nerves, whereas other viruses, such as influenza, infect the body by getting into the bloodstream.

Almost any virus that can enter the bloodstream has a very good chance of crossing paths with the heart – yet white blood cells, natives to the bloodstream, are largely useless in ridding the heart of a virus. This is because the immune system is actually quite slow to respond to a viral infection, according to Sherry.

“Think about when you get a cold,” Sherry said. “You might be sick for a few days or even a week before you start to feel any better.”

According to Sherry, it may take hours or even days for the immune response to develop.

In addition to being the center of everything that flows in the bloodstream, the heart has yet another disadvantage: human heart cells don’t grow back very often. Compared to other organs and tissues, which regularly replicate and replace cells, the average human heart only replaces about half its cells over the course of a lifetime.

Despite being constantly bombarded with viruses and having a limited supply of new heart cells, most of us are doing just fine.

“We fight off these viruses all the time,” Sherry said. “What is it that the heart is doing so differently?”

This question is the driving force of Sherry’s research. Sherry is not only interested in uncovering the body’s defense systems from the perspective of the heart; she also hopes to identify other novel ways tissues of the body employ to fight off viruses.

According to Sherry, the reason it is so difficult to find out exactly how the heart protects itself is because so much is going on during the fray that follows the infection.

To find out how the heart manages to survive, Sherry and her colleagues have taken two approaches. With their first approach, Sherry examined the use of Interferon β in fending off viruses.

Interferon β is a protein that nearly every cell in the human body can generate. From the very moment a virus enters a cell, that cell is marked for death. The only thing it can hope to do is save its comrades. Most of the cells of the body can do this by secreting this protein.

Interferon in itself does nothing to get rid of the virus. It merely alerts cells in the immediate area that there is a viral infection at large, so those cells can begin making antiviral proteins.

Even though most of the body’s cells are capable of secreting a form of interferon, non-heart cells tend to use this only to hold down their fort until the arrival of the cavalry. The rest of the cells in your body don’t rely on interferon as a major part of their immune response.

“The rest of your body doesn’t care,” Sherry said. “You make new liver cells whenever; no big deal.”

But the interferon system isn’t perfect. Viruses are constantly evolving, and many have evolved to the point where they can suppress a cell’s interferon response.

Sherry’s second method for unlocking the secrets of the heart involved taking actual cardiac myocyte cells from mice, and splitting these cultures into three groups.

The first group of cells remained unaffected by any viruses. The second group was infected with a virus the cells could easily dispatch. The third group was infected with viruses that are able to subvert the cells’ defenses in order to do much more damage.

Sherry took what is known as the “proteomic” approach, examining all the proteins secreted by cardiac myocytes, and those found within the cells.

“If you crack open the cells like we did, you’d find all the antiviral proteins because it’s such a potent response. We found [protein Hsp25] in the heart because the heart has to put up pretty much all of its defenses.”

Using this discovery method, Sherry and her colleagues have identified a protein that may be used in the heart’s defense mechanisms. The protein in question is called Hsp25. Hsp25 is by no means a new protein; however, until now it has not been examined as part of the body’s immune system.

Sherry is optimistic but also realistic about the implications of her research.

“The reality is [therapeutic applications] probably won’t be in my lifetime…maybe I’ll be lucky, and it’ll actually end up in therapy,” Sherry said.