Diego Melchor

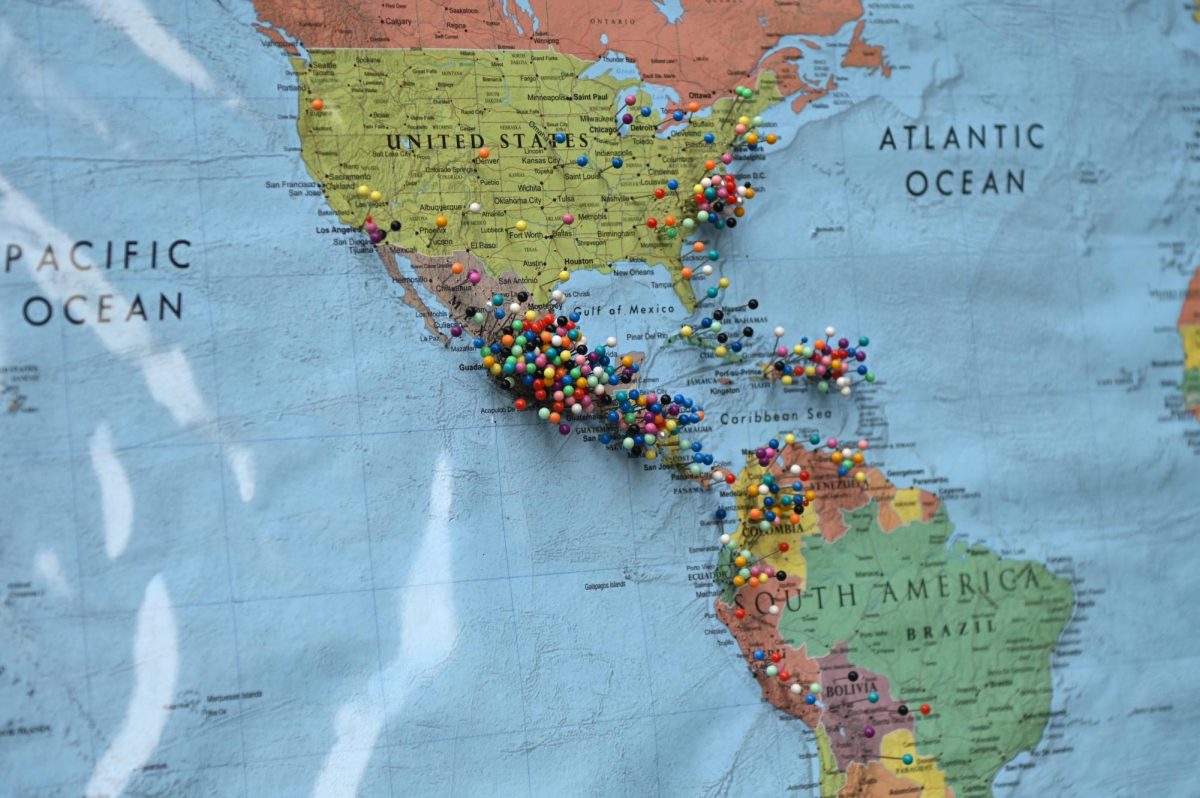

Pinned markers show festivalgoers’ home countries and cities during La Fiesta del Pueblo at Fayetteville Street Historic District on Sunday, Sept. 21, 2025. The event, which draws thousands annually, is organized by El Pueblo to celebrate the pride and resilience of the Latine community.

The Department of World Languages and Cultures hosted a discussion entitled “Embodying Latin America: Youth’s Representational Power in Contemporary Latin American Film” on Sept. 11. The event reflected on the problematic representation within contemporary Latin American film, encouraging participants to be intentional in their film choices as they shape how we interact with each other and the greater community.

Sharrah Lane, an assistant teaching professor of Spanish at UNC-Chapel Hill, was invited to speak about her dissertation, an analysis of youth protagonists in Latin American film.

Her project draws connections between the representation of children in film and broader power structures like colonialism and capitalism. In many films about Latin American stories, there are patterns of violence that symbolize a broader struggle in the region. Beyond that, these simplistic portrayals shape societal biases and individual discrimination.

Lane’s dissertation pulled information and patterns from about a dozen films from the U.S., Brazil, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Mexico and Guatemala. The children in these movies are faced with disintegrated, inescapable struggles, such as financial hardship and parental loss. As a result, a very common character aspiration is to make a new life in the U.S.

Lane noticed that these films often tried to portray progress or movement, but ultimately showed no material change for the protagonists. This pattern of unsatisfying, often violent, endings left Lane feeling frustrated, which led her to further analysis and pattern-seeking within the genre.

“When you’re reading something or when you’re viewing a movie, it’s always good to look at how you’re feeling, because feelings can tell you something about what’s going on,” Lane said. “So this frustration that I felt became a dissertation.”

She found that films such as “La Jaula de Oro,” “Which Way Home” and “El Norte” display a circular system that disregards the humanity and individuality of their protagonists.

“Regardless of where these children travel, their fate remains the same,” Lane said.

Lane said that these films rarely benefit the people they are portraying. Especially with films surrounding indigenous experiences, the framing and marketing is often aimed at the international community, which causes misrepresentation.

While many of the films discussed received critical acclaim abroad, the child actors were not given recognition for their work and, more often than not, fed back into the cycles of violence and poverty their films depicted.

“The directors brought the world’s attention to the issues faced by children and adolescents growing up in these metropolitan areas in Latin America, and these problems persisted,” Lane said. “Nothing was done.”

These patterns are consistent with all the films she analyzed, spanning from 1983 to 2019. And she didn’t have to cherry-pick movies centering children to find ones that had unhappy endings.

“Check any film with a child protagonist in Latin America and you’re gonna see this 90% of the time,” Lane said.

Catherine Larsen, a masters student in the Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages and Spanish programs, had previously met Lane at the North Carolina Conference on Latin American Studies. The two kept in contact after they found their studies overlapped within the topic of marginalized, Spanish-speaking communities.

Larsen said the conclusions Lane makes have implications not only for the media landscape but also for the future of the society it exists in.

“Art tells us something about where society is going, what people are thinking about the culture and the politics and the economics of the moment,” Larsen said.

Lane also discussed the repetition of these victim narratives, showing children subjected to and taking part in violence have implications for wider societal views. She explained that the media shapes how we think about the world and interact with others, so these stories about violent, criminal Latinos are particularly dangerous.

“[Research] can provide an entry way into understanding how to critically engage with media,” Lane said. “We can take a step back and ask ourselves: ‘What am I consuming? Is this problematic? How is it problematic?’ Instead of just being an unaware spectator.”

We constantly consume media that has implications about real world discrimination and hardships. Lane said the important take away is to be aware of our internal biases and treat people as individuals deserving of respect.

Lane advised her audience to not watch the films discussed in her dissertation, as they were riddled with graphic violence and stereotypical stories. Instead, she recommended two films with child protagonists that subvert these common narratives: “Viva Cuba,” a Romeo and Juliet-esque story, and “Havana Station,” a drama exploring class differences in Cuba.