Rory Moon, Graphics Editor

Disability representation in the media has been a concern of advocates for decades. The mass entertainment company Disney has made an effort to include a few characters with disabilities, like in the 2024 film “Out of My Mind” about a gifted child with cerebral palsy who communicates with assistive technology. “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” also features a protagonist with a disability and sheds light on social injustice and ostracism toward disabled individuals.

While these are concrete examples of representation, they place too much emphasis on the characters’ limitations instead of normalizing disability — a recurring theme in many children’s shows and movies.

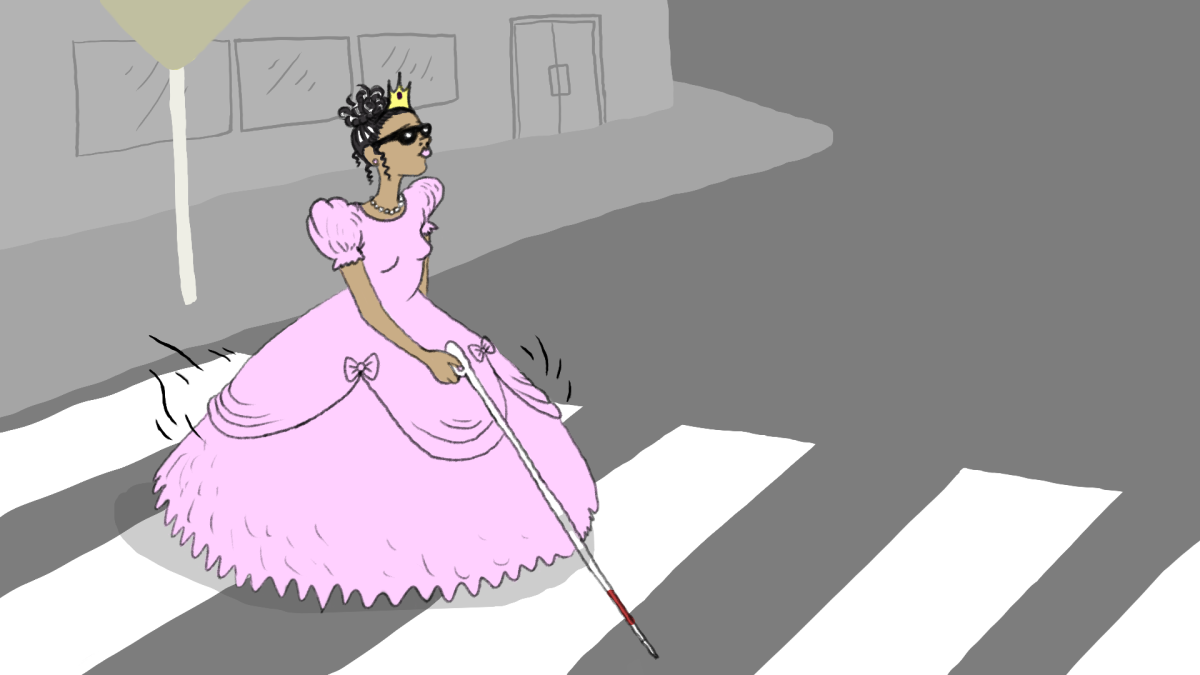

Media affects how people conceptualize “normalcy,” so it’s important to include more than just able-bodied characters. A main character with a disability would promote inclusivity, especially within a major franchise like Disney. Most kids have characters they can relate to in some capacity, but for children with disabilities, it’s more difficult.

In 2015, “Sesame Street” introduced Julia, a girl with autism described as doing things “in a Julia sort of way,” which identifies behavioral differences without painting them negatively. “Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood” features Chrissie, who uses mobility aids, and the show describes what she is capable of rather than her incapabilities.

Daniel Tiger also has a friend on the spectrum named Max who demonstrated the experience of overstimulation. Max used coping skills like covering himself with a weighted blanket, and he has special interests in buses and insects.

I applaud the writers of these shows for including characters with disabilities; however, they made the characters’ limitations their defining attributes.

Emily Kibler, the communications and compliance director for the North Carolina Alliance of Disability Advocates, said a character’s disability should contribute little to the narrative throughline.

“It’s really important to see [a disability] without making it this big, overburdening plot point,” Kibler said.

Another mistake is promoting the idea that disabilities are acceptable once characters find productive uses for them. This flaw is present in “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” where Rudolph is only valued after his physical difference became a solution to the main conflict.

“The issue is it falls in the idea that to have worth as a person with disabilities, you have to have use to other people,” Kibler said.

Christy Cooper, assistant director of the North Carolina Down Syndrome alliance and mother of a child with Down syndrome, said just as disabilities do not define individuals in real life, they should not define fictional characters.

“To center everything on the condition is just a misrepresentation of life,” Cooper said.

Depictions of disabilities can be misinterpreted as mocking, so Cooper said consulting with individuals who have lived experience of the disability is crucial.

“It’s very easy to step into something that’s really offensive, but there are people who can guide you to make sure that you’re taking those things into consideration,” Cooper said.

Kibler highlighted a successful disability portrayal made by Disney in the film “Luca.” One of the characters’ father is missing most of his arm, but it was simply stated that he was born that way and the film moved along.

In “Bluey,” Dougie is deaf and communicates through Australian Sign Language, but there is no overt display made out of his deafness. The superhero themed show “Action Pack” features Ann, who has Down syndrome and can slow time. Ann briefly explains her disability, but spends more time talking about her unique qualities.

“What’s so smart about [the superpower] is that it’s not necessarily something that people know about individuals with Down syndrome,” Cooper said. “They do not go by the clock that everybody else goes by … So it was so clever of them to say that’s a superpower.”

Writers should also avoid framing characters with disabilities’ minor achievements as extraordinary. We shouldn’t have such low expectations of disabled individuals, nor should we use them as inspiration.

I was a summer camp counselor for people with disabilities for several years, and I would get irritated if people would say it was heartwarming to see children with disabilities having fun. Why should we sensationalize something as mundane as a kid going to summer camp? As a person with disabilities, Kibler deals with this on the regular.

“It’s not inspiring that I have a job just because I’m disabled,” Kibler said. “Yes, it’s a little harder for me, but I’m not an inspiration for it.”

As a community, we can promote representation for those with disabilities by supporting media that accurately portrays disabilities. As such, individuals should use the “Nothing About Us Without Us” motto as a general rule of thumb, advocating for including disabled voices in the production of media with disabled characters.

Disability representation within media can cultivate acceptance and inclusion, but it must be done in the best interest of people with disabilities. A main character with a disability in media like a Disney movie would be revolutionary, given their disability is accepted regardless of whether it’s functional to others and as long as there is dimension to their personality.