Rory Moon, Graphics Editor

Many of us text, all day, every day, to anyone and everyone. In 2021 alone there were 2000 billion Short Message Service and Multimedia Message Service messages sent in the U.S.

As a result, texting has become a unique method of communication that allows for more informality than its counterparts, such as email and direct-message.

Over the course of its existence, texting has slowly developed into its own dialect, called “textese.” But does using this shorthand secondary language benefit us? Or is it time that we ditch the informality and care about the way we text each other?

The first ever text message was sent in 1992 from a computer to a mobile phone. At the time, phones did not have full QWERTY keyboards, and though the first phone with such a keyboard came out in 1996, this would not become the standard until the mid 2000s.

Instead of a full keyboard, texters had to use a ten-number keypad to type full sentences, which proved to be time-consuming and annoying. A 160 character limit on all messages exacerbated this. To work around these restrictions, words were shortened to singular letters or numbers, and phrases such as “laughing out loud” were converted to acronyms.

Even after full keyboards on cell phones became standard, even after the release of the first iPhone, users still stuck to the same shorthand dialect through text that had been convenient in years past. Those who were born in the 2000s and after, who never experienced the same keyboard struggles as previous generations, somehow still picked up the lingo.

To this day, that character limit and number keypad haunt every text sent.

Textese, created from decades of text messages, reportedly has a positive impact on literary abilities. Language which falls under the umbrella of textese — including abbreviations, number and letter homophones and creative orthography — should not be penalized or reconsidered when texting.

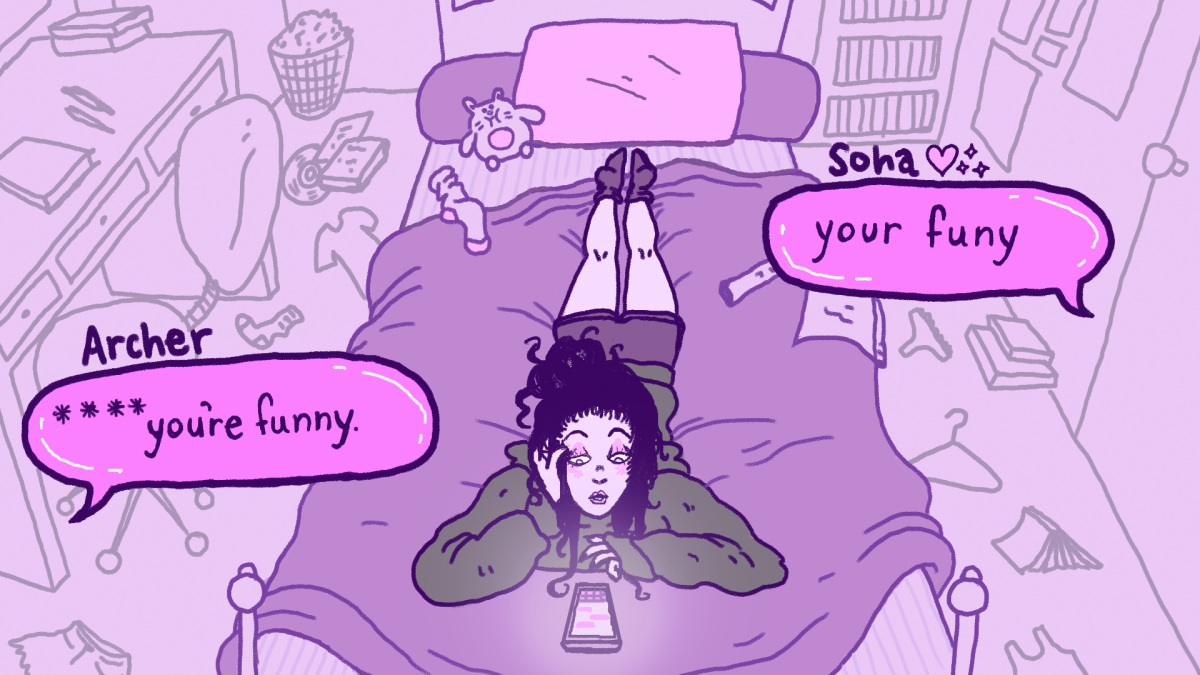

What is not accounted for in textese, though, is the misspelling of homophones such as “you’re,” “there” and “too.”

As an English major, I find myself frustrated and annoyed when someone I am texting misspells these words in particular. While on its own it can be irritating, I find quite often that many of my peers also misspell the same words in their formal work, perhaps due to the fact that they did not understand the differences of such in the first place. I often correct people in these instances for the sake of my peers’ knowledge on the differences between the words, something that I believe everyone who understands the difference should also strive for to better those around them.

Outside of textese, misspellings negatively impact any formal writing work they are present in. When these misspelled homophones present themselves in the formal language of college students, the reader forms a negative impression on the writer’s ability and the quality of their writing. While also likely receiving a lower grade on an assignment.

If the informality of textese begins to bleed into formal writing, it is best to reconsider the notion of ignoring homophone misspellings in text messages. Fixing these errors in texting takes a few seconds at most, and understanding why the correct version should be used and the differences between each homophone will contribute positively to any formal writing.

Texting should be an informal outlet of communication, as it has been for the past few decades. However, as higher education students, we should strive to understand the differences between homophones and use them correctly throughout our writing, whether informal or not. There is simply no gain from using them improperly.