Rory Moon, Graphics Editor

At NC State, owning a parking permit has become a privilege, not a right. Permits cost hundreds of dollars per semester, yet students often rely on luck to buy one in the first place. For commuters, who don’t have the luxury of walking from their dorms or apartments near Hillsborough Street, this feels especially cruel.

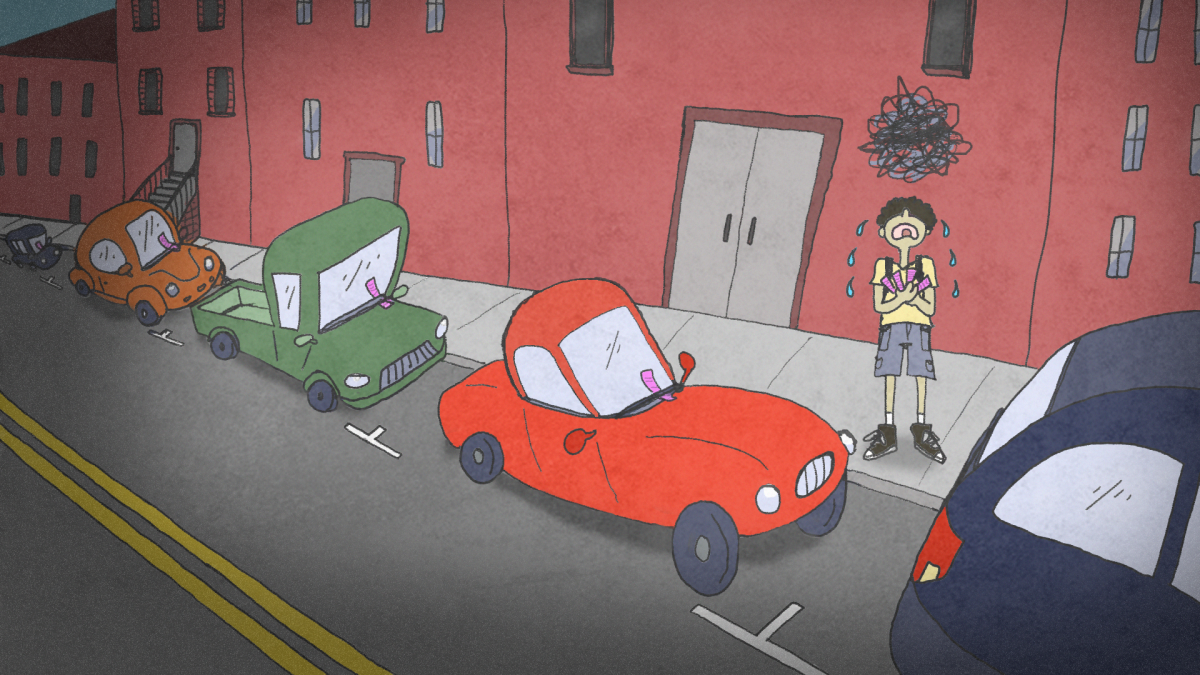

Between sky-high costs, random lotteries and limited spaces, the University’s parking system has become a daily obstacle for students who decide to save money and opt out of living on campus.

Caitlyn Blakelock, assistant director for parking services and operations, said the high prices are not arbitrary, but the result of how NC State funds its transportation system.

”We are a receipts-supported unit on campus, which means we do not receive any state or federal funding for our operations,” Blakelock said. “So it is entirely our responsibility to take care of all of the parking lots and keep the system running.”

That independence means revenue coming in from student permits goes back into maintenance, staffing and operations, but that doesn’t make the system feel any less punishing for the students paying into it.

“All of the money that comes from parking permit sales goes back into the maintenance for the facilities, as well as the administrative costs of our department,” Blakelock said.

Still, the logic behind the lottery system is baffling. For many, it’s not just inconvenient, it’s anxiety-inducing. Imagine registering for classes, planning your semester and then finding out you might not even have a convenient way to get to campus.

Connor Jones, parking services manager, said the process really is both random and statistically fair.

“When students sign up for the lottery, their name is entered into the software and it is a random drawing,” Jones said. “We click a button, and through math I don’t know, it is totally and truly random who gets selected.”

But random isn’t the same as equitable. Why should a student’s ability to park depend on software randomization? Commuters aren’t all entering from the same starting line. For many, parking access determines whether they can attend class, work or even afford to stay at NC State in the first place.

Blakelock said the old model was even worse.

“We used to sell resident permits on a first-come, first-serve basis and one of my colleagues likened the process to purchasing Beyoncé tickets because they sold out so fast,” Blakelock said.

Now, students who lose the lottery are pushed to Park-and-Ride lots, a less convenient, more time-consuming option.

”We have multiple Park-and-Ride options that are free for commuters,” Jones said. “Carter Finley Stadium and Spring Hill Park-and-Ride are both served by the Wolfline, which is also free to use.”

But what’s framed as an “option” often feels like the only one. Between delayed buses, full lots and the added time it takes just to get from your car to class, it’s less a backup plan and more a compromise forced by circumstance. Students shouldn’t have to wake up an hour earlier or gamble with bus schedules just to get an education.

Meanwhile, the cranes keep moving and construction keeps growing. New buildings, new housing but no new parking. Blakelock said that the university’s long-term approach to parking is shaped by its Physical Master Plan, which lays out how the campus will grow in the near future.

“The Physical Master Plan requires that parking is moved to the perimeter of campus, and then people use buses, biking or walking to get to the interior,” Blakelock said. “As the university facilities department starts to implement some of those master plan programs, that will impact parking and will cause us to actually lose parking.”

Demar Bonnemere, communications manager for the transportation department, said that the plan is more flexible than it might appear.

“It’s more of a guide. It’s not an actual plan,” Bonnemere said. “As time goes on and as funds come available, it might actually change. So we can’t say we’re going to build a deck here, because something may change in the university.”

That flexibility might offer some hope, and the department recently began to evaluate what’s next.

“We just started a parking study on campus,” Blakelock said. “We are looking to the future and what that might hold and how we’re going to respond to that.”

But for now, the present reality is hard to ignore. Parking at NC State has become a privilege earned through luck, money or proximity, not fairness.

Expanding Park-and-Ride options, improving Wolfline reliability and coordinating more closely with city transit would make commuting less of a gamble and more of a guarantee. Wolfline routes can be more frequent and dependable so students don’t have to guess when to leave home or risk missing class because of inconsistent times.

This also means keeping Park-and-Ride lots well-lit and in areas that feel safe late at night. It absolutely means lowering the cost of parking permits because access to campus shouldn’t depend on whether you can afford it.

Until parking is treated as a necessity, not an afterthought, the system will keep leaving students behind. If the University truly values accessibility and inclusion, that commitment needs to extend to how students get to campus, not just what happens once they’re here.