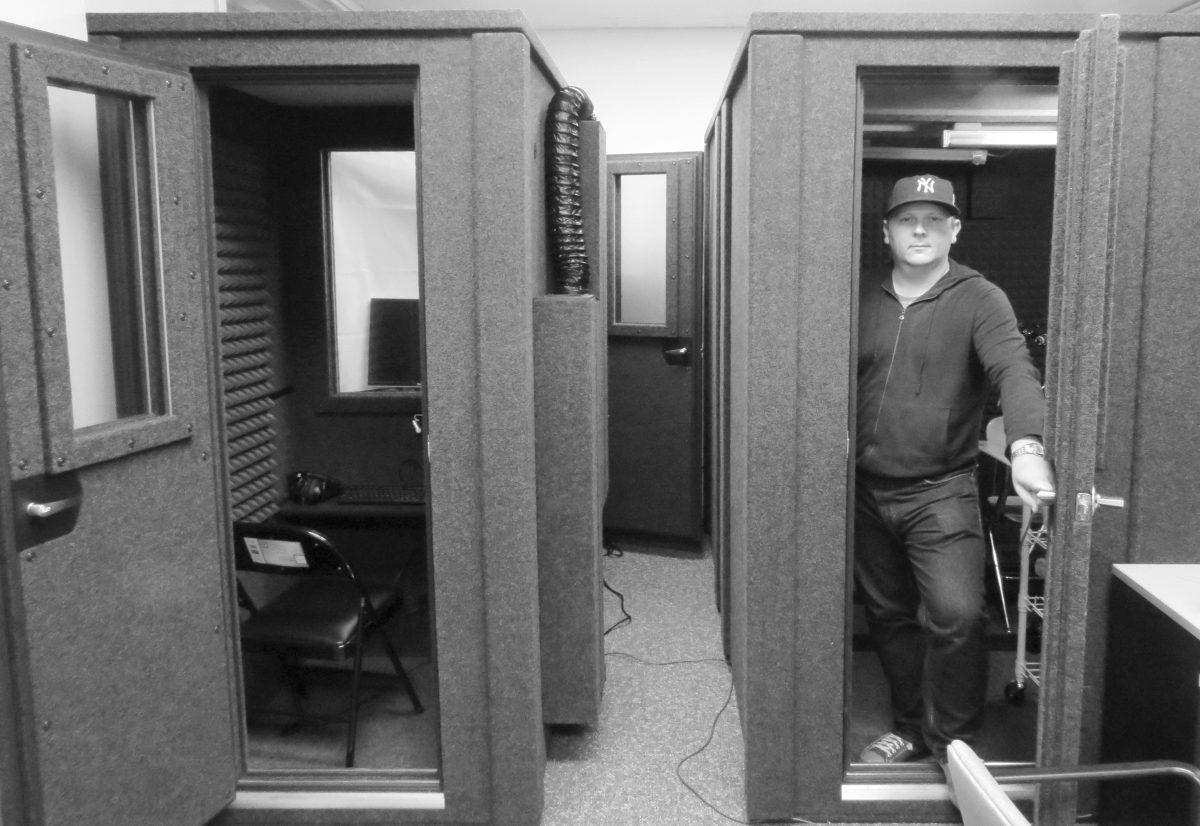

Graduate student in linguistics Eric Wilbanks points to the right side of the screen showing where the tip of the tongue is. He stands in a black soundproof box inside a room in Cox Hall along with Jeff Mielke, head of the phonology lab, Amy Hemmeter a graduate student in English and Nicholas Membrez-Weiler a graduate student in the Department of Sociology & Anthropology. They watch Mielke’s tongue, through an ultrasound, slide around in his mouth. This all serves to demonstrate how they would observe the way a person physically makes words and how the tongue moves to make sounds, which wiggles more than you might expect.

Mielke, along with five graduate students and one postdoctoral researcher, observe and record physical movements that the human mouth makes to produce language.

The project records volunteers speaking with a camera to observe how the lips move, an ultrasound to record the movement of the tongue, an electroglottograph to measure how much the vocal chords move and an airflow mask to record nasal airflow as the person spoke. A frame holds volunteers’ heads still as they speak to provide a more accurate look at how they form their words.

“English has a large number of different vowels,” Mielke said. “We think it has five but it’s more like 12 or 14 and different versions of English have slightly different versions.”

According to Mielke, he and his team collect data for a laboratory in Paris called the Laboratoire de Sciences Cognitives et Psycholinguistique which is collecting data from different parts of the English-speaking world. Their interests lie in how language works, how people perceive it, and how people produce it.

“One aspect of the program is the language attitudes, looking at language attitudes toward the South and language attitudes toward features of Southern speech,” Wilbanks said.

Mielke said people naturally converge to speech they are directly exposed to if exposed to someone of like-speech or diverge their aspects of speech when talking to people who speak different, and he hopes to do an experiment later this semester to observe how much people converge or diverge their speech. According to Mielke, converging speech into something similar to another person’s is an implicit measure of people’s language attitudes.

“We are taking advantage of the fact that North Carolina has a mixture of different dialects,” Mielke said.

According to Mielke, North Carolina is one of the top destinations for people from the North to move to because of the Research Triangle Park. North Carolina is an excellent place to research speech production and language attitudes because of the great number of dialects present, including the Outer Banks dialect, East North Carolina dialect, Appalachian dialect, Cherokee dialect, Lumbee dialect, general southern and Virginia dialects, African American English and Northern dialects.

“The more we know about specific examples about how people use language in specific situations, the more we can generalize about cognitive processes, how the brain works, and how we process language,” Wilbanks said. “An important focus of the [linguistics] department is the social aspect of it, how do people use language in social situations for social purposes—or just language for language purposes—and how social things affect that.”

According to Mielke, NC State has recently added a doctorate program in sociolinguistics. One of the program’s researchers, Nicholas Membrez-Weiler, is not part of the linguistics program in the English Department at State but the Department of Sociology & Anthropology. Though the data collection for the French Laboratory is ending, linguists will always be trying to collect data on speech patterns and formations.

“The study of language will go on forever,” Mielke said.