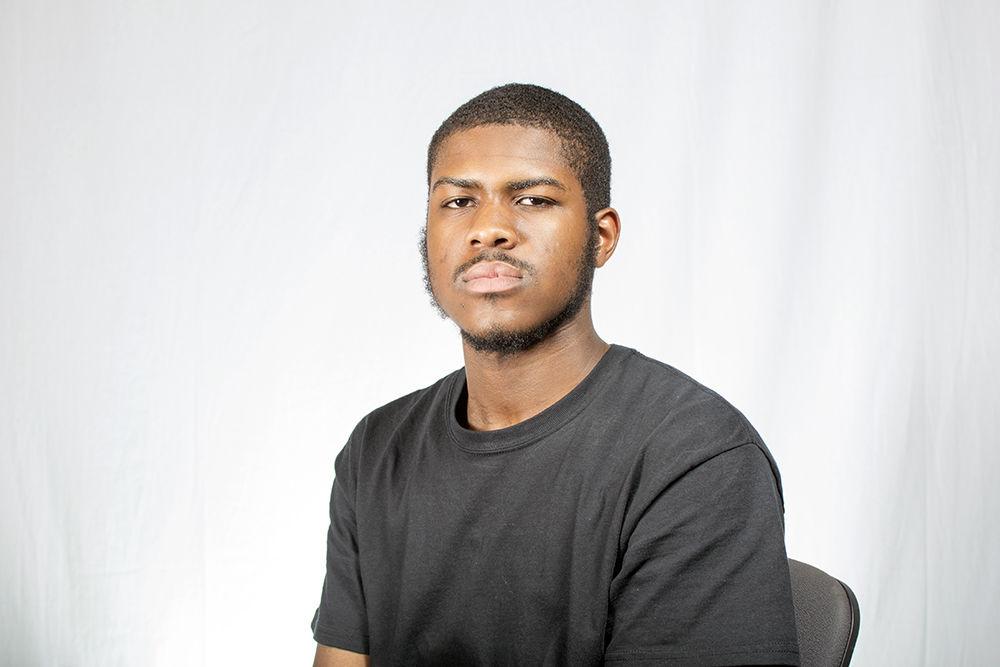

Rasheed Harding

For most of us, finals are right around the corner. There is something about a final test, paper or presentation that seems to brings the past into focus. Everything has led up to this point, and amidst the studying and revising we need to allow for evaluative, spontaneous reflection on the decisions that got each of us where we are.

Most of this reflection falls under two categories, namely “what was done” and “what was learned.” Our courses and extracurricular activities demand much of our attention and dedication (what was done). Thus, we develop an analytical focus on our current behavior and how it may need to change in light of our experiences (what was learned).

This is especially applicable to our courses. Throughout the semester we are bombarded with incentives to learn how to navigate different subjects, class formats and teaching styles, and we more or less attempt to adapt to those academic pressures and environments to the best of our abilities.

During a recent late-night homework binge, my eyes drifted over to the dusty textbook that I had yet to open. Naturally, I reflected on this.

At the beginning of each semester, whether motivated by research or trial and error, a significant number of students are expected to exhaust all options before spending a dime on their “required” textbooks. There are many alternatives to the overpriced bookstore, like renting/buying used books from Amazon or Chegg or opting out of purchasing the newest edition of a book you already own.

Unfortunately, these rigorous efforts seem pointless once you realize that neither you nor your professor ever referred to those books all semester long. How professors, as learning resources themselves, can so neglectfully require the purchasing of inherently useless books is beyond vexing.

Due to any professor’s prior knowledge about the information we will need to pass their courses, they should avoid requiring that we purchase a textbook that will add no significant value to said courses. At the very least, whether they are bound by policy or personal recommendations, they should take strides to let students know ahead of time if said books are worth purchasing.

A range of economic perspectives have been applied to dilemmas of this nature. The bottom line is the lack of interaction between the professor who chooses a book and the publisher who sets its price. The student bears the cost of the textbook, so the professor has no incentive to consider its overall usefulness relative to its price. A recent-edition hardcover with a pristine cover and an access code sounds great to everyone except the student buying it.

NCSU Libraries, as well as countless identical sources, have noted how students spend on average around $1,200 per year on their textbooks. Over the last 30 or so years, textbook costs have outpaced inflation by close to 300 percent.

According to Tyler Kingkade of the Huffington Post, a U.S. Public Interest Research Group survey of college campuses revealed that 65 percent of students avoided purchasing a book due to its cost, while 94 percent of them believed their grades would be impacted by this decision.

This report, published by the Center for Public Interest Research, analyzed and outlined the intricacies of the college textbook market and provided economically appropriate steps students should take in response to its complexity. The report explains how open-source textbook projects, such as OpenStax and OpenTextbooks, “are gaining significant traction as an innovative replacement for print textbooks. More than 2,500 professors have agreed to adopt open-source textbooks in their classrooms.”

I find it personally disheartening that the cheapest universal workarounds typically involve transitions to digital media. The notion that the computer screen is our literary sanctuary has permeated our solutions to issues of this nature, and this ultimately distracts from the real problem: every course doesn’t need a book.

I’m currently enrolled in ST 350, and the “required” book I rented hasn’t helped me yet with a single study session or assignment. I opened it once, and the information within deviated completely from the style of the class. The professor himself provided a mountain of information and resources in the form of PowerPoint slides (which he taught everything from), problem sets, past tests and study guides. Everything was online, all of it free.

However, on day one, the professor not only failed to mention the book’s uselessness, but he also went the extra mile and informed the class of two more resources we “needed” to buy.

The first was, of course, a WebAssign access code, which I couldn’t do any of my homework without. The second was a supplemental “course pack,” which ended up being nothing but a glorified exercise booklet filled with word-for-word material that was taught in class. I never bought the course pack, and I regret nothing.

What is so irritating to me is that I can’t imagine what stopped him from telling us how unnecessary purchasing a book or course pack would be. Any professor who uses their own research and ingenuity to successfully teach the subject’s essentials without a $200-300 hardcover is basically a superstar in my book.

To my fellow students, we can easily defeat this defective teaching culture. Give feedback to your professors if you ace their class without the book. Our teachers should no longer “require” textbooks if they don’t expect anyone, including themselves, to consult them.