Carter Pape

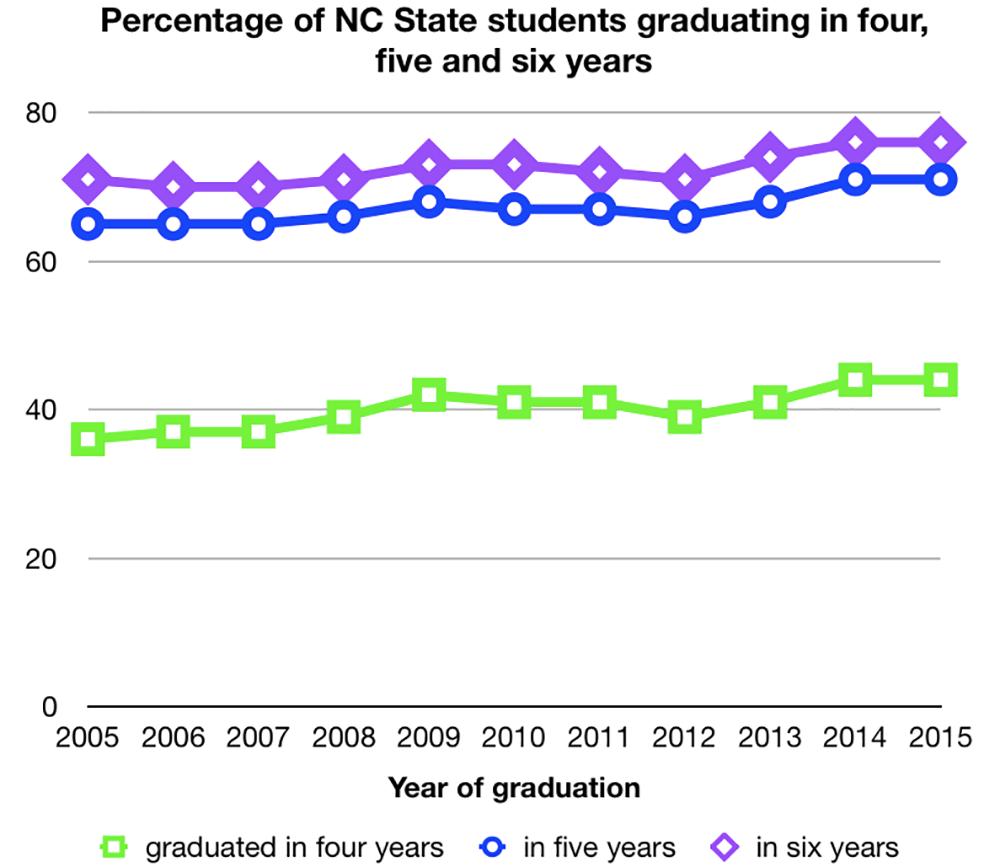

This graph shows graduation rates per year. Educational institutions receiving federal aid are required to report graduation rates per year. These graduation rates are broken down to keep track of students graduating that year who did so in four, five or six years.

Overall retention and graduation rates of NC State students have grown annually for the past five years, thanks to longitudinal efforts across various NC State campus organizations to keep increasing undergraduate graduation and persistence rates.

Among these organizations, the Office of Institutional Equity and Diversity as well as Multicultural Student Affairs (MSA) are focusing on increasing undergraduate graduation rates for students of ethnic and racial minorities.

“Underrepresented students make up a small percentage of the student body and their graduation rates are at a record high,” said ssaTracey Ray, assistant vice provost for student diversity. “Differences between NC State graduation rates and peer institutions are due to a number of factors, such as: NC State has a high population of students that qualify as Pell Grant recipients or come from a lower socio-economic status… NC State has a high population of students that work — many well above 20 hours per week.”

As of spring 2017, approximately 29 percent of undergraduate NC State students self-identify as members of ethnic or racial minorities.

According to Ray, many factors affect changes in graduation rates at NC State University including personal finances, financial aid, work schedules and one’s relatives having graduated from a 4-year university.

In particular, changes in graduation rates can fluctuate substantially in smaller student populations compared to larger ones. This is especially true for students self-identifying as “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander” or “American Indian or Alaskan Native,” which are the smallest racial or ethnic groups at NC State.

Because of this, graduation rates in smaller populations are not as statistically robust as those in larger populations. To best interpret and foster increasing graduation rates at a university, administrators must provide weight to both the number of students in a population graduating as well as the percentage of a population graduating.

Since beginning her time at NC State this summer, Nashia Whittenburg, director of MSA, has made a point of developing strategies to further increase and sustain undergraduate graduation rates among students of racial and ethnic minorities. In light of “record-high” graduation rates, Pacific Islander, African-American and American Indian male students continue to fall beneath NC State’s average 6-year undergraduate graduation rates by nearly 10 percentage points.

According to Ray, students in this group are particularly disadvantaged compared to students of other races and ethnicities at NC State, as many of them are first-generation students. Nearly 50 percent of incoming African-American and American Indian students at NC State are first-generation, first-time students.

For Whittenburg, being a first-generation student entails dealing with the academic rigors, professional nuances and financial hardships of postsecondary education without familiar guidance and experience. MSA’s purpose is to promote student success alongside student retention and graduation, particularly in ethnic and cultural minorities, according to their website.

For ethnic minority students, Whittenburg said that a variety of conscious and unconscious factors including feeling like “the only one” of an ethnic group or race in their department, homesickness and microaggressions are commonplace and can diminish graduation rates.

“[Success] is about the students’ ability to pay and faculty giving underrepresented students the opportunity to apply to internships, scholarships and other opportunities that they aren’t passing on to all other students,” Whittenburg said. “… Having special office hours and having special relationships with students outside of the classrooms.”

Whittenburg noted that these factors, including racial bias, can profoundly affect graduation rates among students of ethnic minorities. She recalled one instance of such bias between a professor and a group of students of color during her time as academic advisor in the Equal Opportunity Program at Stony Brook University.

“[The students] didn’t know that their professor was having Sunday teas with other students in their lab to go over the specifics of their lab,” Whittenburg said. “They created their own network of students of color to help support each other through that. Sometimes bias is [subconscious]. The faculty member doesn’t even identify what they have done to divide the students based on race and ethnicity.”

According to Whittenburg, well-trained faculty should be educated about biases that can diminish the potential of minority students as well as behaviors that can encourage their success. At NC State, Ray and assistant equal opportunity officers David Elrod and Dave Johnson train all university staff and faculty on diversity and creating “a positive environment for everyone that lives and works here,” according to Whittenburg.

Whittenburg hopes to continue expanding programming with other centers on campus to better support students in ethnic or racial minorities at NC State. Ray expects to continue research and targeted programming to increase university graduation rates and encourage further equitable access to education opportunities for all students.

“You bring in more students, you retain more students, you make more money,” Whittenburg said. “It makes weight for what your degree means. I’m looking forward to doing more strategic planning with my staff, looking at where and how we can be a positive influence.”