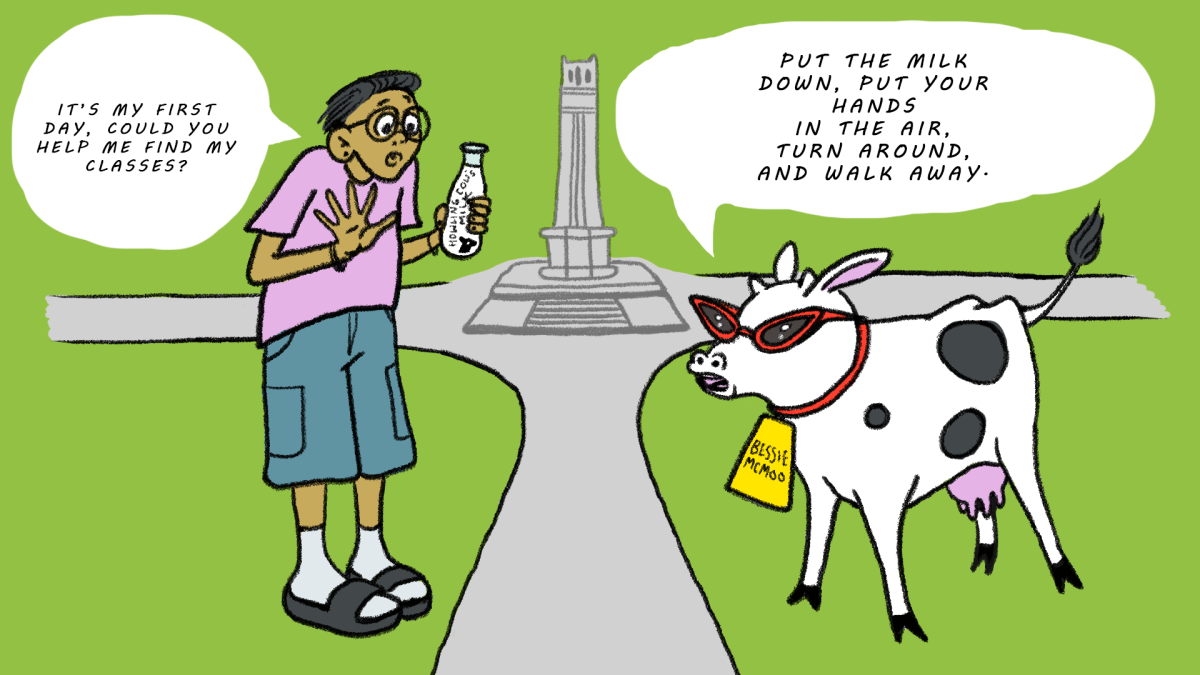

At the beginning of each semester, students at NC State are greeted with emails from our bookstore advertising their “best prices and selection.” As a first-year entering college, though, it doesn’t take much time to realize just how much you want to avoid the bookstore at all costs, largely because of the increased prices. According to the National Association of College Stores, approximately 21.6 cents of every dollar spent on a new textbook goes to the bookstore.

Campus textbook buyback programs often do not offer students reasonable prices. The reason for this is the immense supply of textbooks at the bookstore as well as them opting for new editions. When this happens students are basically stuck with a textbook they no longer need and the longer they hold onto the book the less likely it is that they will get any reimbursement.

As technology advances at NC State it generally seems that textbooks are not much of an investment. As the transition from print to digital progresses, teaching styles are also starting to become more digitalized in nature as well. The bulk of class information is presented on PowerPoints that are often available online. Many readings for classes are available through electronic articles from the library that are found in course reserves.

However, it still seems that professors are hesitant to advise you to skip buying the book even if it’s not necessary.

Nonetheless, students have spent less and less money over the years on new textbooks, pushing publishers to increase their prices even more. Textbook companies like McGraw-Hill are changing their approach to this issue by creating electronic, interactive textbooks that will not need to compete with the used textbook market since they cannot be sold. Access codes are also another avenue publishers have pursued since they terminate at the end of the semester or year and can no longer be used.

Only about five main textbook publishers control about 80 percent of the market. This incentivizes publishers to produce new versions every two or three years, even if the content has barely changed. For a single semester, current students on average spend about $600.

It is important to note that this figure does not count buying used or renting and prices vary semester by semester, especially if you have to buy a new edition. Textbook prices have risen higher than overall inflation for the last three decades and it is no surprise that students have started looking for alternatives.

While purchases still outpace rentals, alternatives to buying from publishers are becoming more and more popular. NC State’s Alt-Textbook project offers small grants to faculty to create open textbooks as well as other open educational resources. In the program’s first year, it saved students over $200,000 in textbook costs. In 2009, NCSU Libraries partnered with the Physics Department to provide free access to several of their required textbooks. While these steps are in the right direction to improve NC State students’ access to education, more needs to be done.

Online options like Amazon or Chegg allow you to rent textbooks at a fraction of the cost it takes to rent or buy them from the bookstore. It is cheaper to rent than to buy books and sell them after the fact, thus more and more students are turning to this option. OpenStax is another great website that offers free textbooks on a variety of subjects.

If you want to buy used textbooks, apps like OfferUp are good places to look. If you don’t want to rent or buy, renting the textbook from the library for a few hours or using the copier are easy options. The library also has electronic articles that are found in course reserves for supplemental material for courses.

While it varies by degree, in my experience the majority of textbooks assigned for classes are hardly ever cracked. Syllabi urging students to buy textbooks are misleading, often resulting in students paying for the books before they realize the teacher had no intention of ever using them.

Many professors prioritize content over cost when assigning them, giving students limited purchasing options. Approximately one out of ten students fail a course each semester because they cannot afford the required course materials.

Our current system of depending on professors to do the research about how much the textbook they are assigning costs is not sufficient. I would argue this learning curve has been somewhat slow and it would be beneficial for teachers and schools to convert to open educational resources that allow students to access the content for free.

If universities are not willing to go this route, professors should be required to prove they have looked at alternatives if books exceed a certain price point. Students struggling to make ends meet are faced with financial tradeoffs that increase as they reach upper-level classes where deals on course materials become much more difficult to find.

Those that rely only on their own income supplemented by financial aid or student loans face unbelievable financial stress just to get by. Now, add that onto the stress of being a full-time student who is facing a financial tradeoff between a month’s worth of groceries or a new textbook, and it’s clear the playing field is not level.

The cost of textbooks is just another way that our current system exacerbates inequality. The growing cost of higher education is already creating unbelievable financial burdens, materials for classes should not follow suit.

Learning styles vary and students should choose whatever option makes the most academic and financial sense to them personally. I learn much better with academic articles and have never been one to enjoy the pleasures of reading a textbook. However, if you are the type of person who needs to highlight or write in a new book and that enriches your learning experience, buy the dang book! Otherwise, rent it or buy it used and revel in your money saved.

In the meantime, I am hoping NC State will continue to fund initiatives to make educational resources more open and available to provide its students an equal opportunity for learning.