“From the mounting gloom, crippled, emaciated patients oozing disease began plodding toward us like the undead.”

No, this isn’t a sci-fi book. These are the words of Greg Campbell’s 2001 novel from a burnt-out hut of a “field hospital” for starving, dying child soldiers in Kailahun, Sierra Leone, a village with more than 30,000 starving refugees.

The scene was not an isolated one after more than a decade of death in the country — a war not for hate, but for control over the nation’s rich diamond mines.

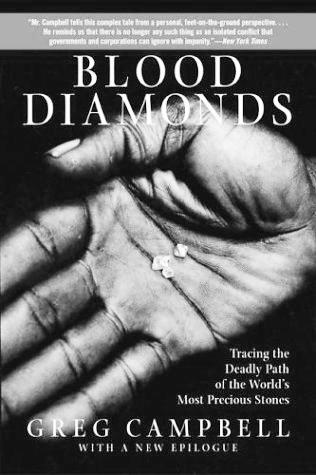

Yet the world’s diamond industry willingly supported the conflict, as told in Campbell’s Blood Diamonds: Tracing the Deadly Path of the World’s Most Precious Stones.

Greg Campbell is an award-winning author and freelance journalist. He has authored four books including his latest, Pot, Inc., a first-hand look into the expanding medical marijuana industry that is now in 16 states.

His life-long love for writing became a published reality through Chris Hondros, a former Technician and Agromeck photographer. Hondros talked his editor into sending him to the 1993 inauguration of President Bill Clinton in Washington, D.C. — but he needed a reporter.

“Chris and I were close friends, and I was studying journalism at UNC-Greensboro,” Campbell said. “He just called me up and said, ‘Hey let’s go. We’ve got an assignment to go cover the inauguration for the Technician.’”

And so began his journalism career.

Just three years later, he was traveling to Bosnia to cover the reunification of Sarajevo for his first book, The Road to Kosovo. Immersing himself in the reeling, hate-filled region, he became what he is today: a conflict reporter.

“That was my first experience, and I was interested in going back — especially looking at conflicts that were not well publicized, that people were just unaware of,” Campbell said.

Enter Sierra Leone, a small West-African country dripping with diamonds and the blood from a genocide unique to the region — for economic reasons, not racial.

In the early 1990s, rampant poverty and government corruption helped the rebel Revolutionary United Front gain public support, but the RUF took over the mines, slaughtering civilians and enslaving the rest.

The world’s diamond trade willingly bought cheap diamonds from the RUF, knowing it used the money for weapons. In 2001, rebel groups from around the world were responsible for as much as five percent of the diamond market — 80 percent of which was sold in the United States.

But until Campbell and Hondros went to Sierra Leone in 2001, the world was either oblivious or compliant.

Campbell quickly became an expert on conflict diamonds. He was only in Sierra Leone for five weeks, but he might have been there five years. His narrative, literary approach seamlessly switches between his own experiences and those of others, telling the life story of a broken nation and industry in striking detail.

“That’s just always been a characteristic of my writing, I think,” Campbell said. “I write really natural like that, and since I enjoy reading that kind of writing style, it’s very enjoyable to actually write that way.”

By the time Campbell arrived in West Africa, the United Nation’s weak peace efforts had made much of the country passable for the first time in years. He met proud RUF killers, hardened diamond “businessmen” and colonies of limbless people who were walking reminders of the RUF’s response to a president’s plea to “join hands” for peace.

With the Sept. 11 attacks occurring during his research, Campbell discovered just how important the seemingly isolated conflict had been.

“[Al-Qaida’s] bank accounts were immediately frozen all across Europe and the Middle East,” he said. “And yet they had [diamonds] from Sierra Leone that they could spend on future training, future attacks and so forth.”

When Blood Diamonds was published, detailing the compliance of dozens of countries and companies and the lackluster efforts by the UN at peace and reform, it changed the way the world bought diamonds.

“I’m not certainly crediting myself with changing the world, but I definitely contributed to it,” Campbell said. “I brought information out into the public view where this very, very vibrant debate went on after the book was published.

“You can’t underestimate the power that you have as a journalist to be able to perhaps make a bad situation better just by reporting about the bad situation,” he said.

“You’re there as a witness.” Since Blood Diamonds, Campbell has continued conflict reporting. He and Hondros went to Libya in 2011 to cover the rebellion against Moammar Ghadaffi.

“That’s one of the most fundamental stories we have as a race of people — people overcoming oppression, throwing off their bonds and rising up to embrace self-governance,” Campbell said. “And to be there, as one of the people who were chronicling it for all of history — that’s an amazing responsibility.”

The dangerous nature of conflict reporting finally caught up to the two friends. Not long after Campbell left Libya to return to the United States, Hondros was killed in a mortar blast, a loss that deeply affected Campbell and many at N.C. State.

“That’s a risk that has always been there, and unfortunately, people have to take those risks in order to have this information to provide to the rest of the world,” Campbell said. “Somebody’s gotta do it.”

Campbell returned to Sierra Leone later in 2011 for the 10th anniversary of the book, adding 50 pages to its latest edition on the progress of the country and the worldwide push to end diamond smuggling. Both are off to rough starts. The fighting is over, but plaguing the country is all-too-familiar corruption and poverty.

While international mining companies had modern health facilities inside their razor-wire compounds, Campbell watched a local doctor perform a hysterectomy with little more than sunlight and local anesthetics.

“The conditions that led to the war in the first place are still really prevalent,” Campbell said. “It was kind of disheartening to see that the country hadn’t really taken advantage of the opportunity for peace like it could have.”

As he looks forward in his career — hoping to expand his storytelling skills through filmmaking — he will always carry a piece of Africa with him.