A combination of government policies, utilities companies, startups and activist groups are increasingly defining the path to renewable energy in North Carolina.

During the last seven years, Duke Energy, the sole provider of energy in North Carolina, spent $3 billion for renewable generations, according to Randy Wheeless, communication manager at Duke Energy. Last month, Duke Energy announced it would build three utility-scale solar-power projects, totaling 30 megawatts, in Eastern North Carolina.

In 2007, the North Carolina General Assembly passed the Renewable Portfolio Standard, which required that 12.5 percent of all energy must be generated by renewable sources by 2020.

“We’re working very hard to meet those standards,” Wheeless said.

According to Wheeless, Duke also has a growing portfolio for increasing the state’s generation of solar power.

North Carolina Solar Center Executive Director Steve Kalland said the renewable energy climate in North Carolina is currently “a mixed bag” of solar, wind and biofuel sources. However, solar power stands apart from the rest as the cheapest and most convenient source of renewable energy for the state.

“The biggest piece of sustainability in North Carolina right now is solar farms,” Kalland said. “The [RPS] law, along with 27 other similar laws in other states, has been extremely effective in driving down the price of solar energy. These solar-farm systems are going in at a rapid pace.”

Wind energy, on the other hand, is more complicated, Kalland said. Military officials have said they’re worried wind farms could create barriers to their training.

Smaller startups are also making their impact on the renewable-energy scene, in the form of consultations and microgrid technology, according to Kyle Barth, a senior in electrical engineering and intern at Green Energy Corp.

A microgrid can connect and disconnect from a main power grid, enabling it to operate to provide power for itself without impacting the macroprovider, Barth said.

“Microgrids aren’t exactly anything brand new,” Barth said. “They are just a different way for configuring your system.”

Microgrids are most often used at industrial campuses, college campuses and military grids. They are also used at off-shore drilling rigs.

“With very remote areas, grid connection is not an option,” Barth said. “You’re all but required to provide your own energy resources. On industrial or college campuses, you usually have continuous ownership of one entity over a pretty large area. You have a large demand for power in a small area, so sometimes, offsetting that demand with some self generation can be advantageous.”

Barth said there are currently about 30 true-working microgrids in the United States. However, projections show that this number could increase to more than 300 in the coming years. Because microgrids power a small area, operators can have a better idea of power usage, Barth said.

“We don’t consume a constant amount of power,” Barth said. “Every time you flip a light on or off, you’re changing the net load of the building or the net power demand. That demand curve tends to be pretty repeatable. You can actually build your microgrid to better meet that load specifically.”

This knowledge allows a company to create energy supply based on demand, and not the other way around, making the process more reliable and economically-friendly. Also, because microgrids can use a variety of sources, including solar, battery energy storage and natural gas, they tend to be more sustainable, Barth said.

In addition to new technology, legislation is affecting change in renewable-energy use. William Kinsella, an associate professor of communication at N.C. State who specializes in science and technology policy and rhetoric, said there are two kinds of states: regulated and deregulated. In a deregulated state, such as California, different companies compete on the energy market, and the company that offers the lowest price succeeds.

Southeastern states tend to be regulated states, or states in which a governing body such as the North Carolina Utilities Commission decides what company or companies will provide energy to consumers, Kinsella said.

“In my view, there are really urgent needs to move toward clean, sustainable energy technology,” Kinsella said. “The necessity is going to become so undeniable that it will happen. But the question is, how fast will it happen?”

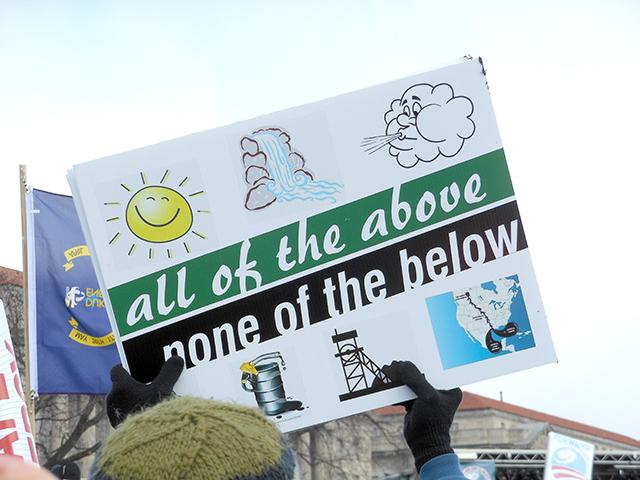

Because public policy plays such a large role in North Carolina energy, activist groups are seeking to raise awareness about government interactions with utility companies. Fossil Free N.C. State, an environmental activist group that seeks to eliminate dependence on fossil fuels in the UNC-System, uses demonstrations to educate people on campus about renewable energy, said Hannah Frank, a member of Fossil Free and freshman in nutrition science.

“It’s hard to impact policy, because that can be driven by who has money,” Frank said. “Activism is important because it gives people a chance to voice their opinion.”

Fossil Free members have met with Duke representatives to discuss a renewable energy tariff and voiced concerns at Duke shareholders meetings or at public forums hosted by the N.C. Utilities Commission. Frank said one of the club’s main goals is to impact North Carolina policy by joining forces with other members of the UNC Board of Governors.

“The UNC-System is a big Duke Energy customer,” Frank said. “We have such a powerful voice, not as a few college kids but as a customer.”

Kinsella said he thinks public voice will be essential in deciding the direction that energy policy will move toward.

“Not every single person should become interested, but there must be a substantial public conversation and enough different points of view so all possibilities can be considered,” Kinsella said.

Critics have said renewable energy is only profitable to companies because of government subsidies, such as tax incentives. However, Kalland said this argument is not quite true. State tax incentives, combined with federal incentives creates a healthy incentive to drive sustainability forward, but all resources have incentives, he said.

“Coal, for example, has incentives in the mining and extraction side,” Kalland said. “Also, if the federal government hadn’t used eminent domain to build railroads across the country, it would be much harder today to use coal as an energy source. Solar incentives are more obvious, but only because they are new and haven’t had time to bury themselves in the tax code.”